The battle against Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) has been going on for years, with developers and security experts constantly seeking new and improved methods to protect web applications. The most common way is using a sanitizer, meant to manipulate untrusted user input in a smart way in order to prevent any unwanted markup. Implementing HTML sanitization on the server side sounds logical at first glance, but this strategy has often fallen short. In this blog, we will demonstrate the limitations of relying solely on server-side sanitization, and why this is one of the main root causes of bypasses.

Background

The Problem

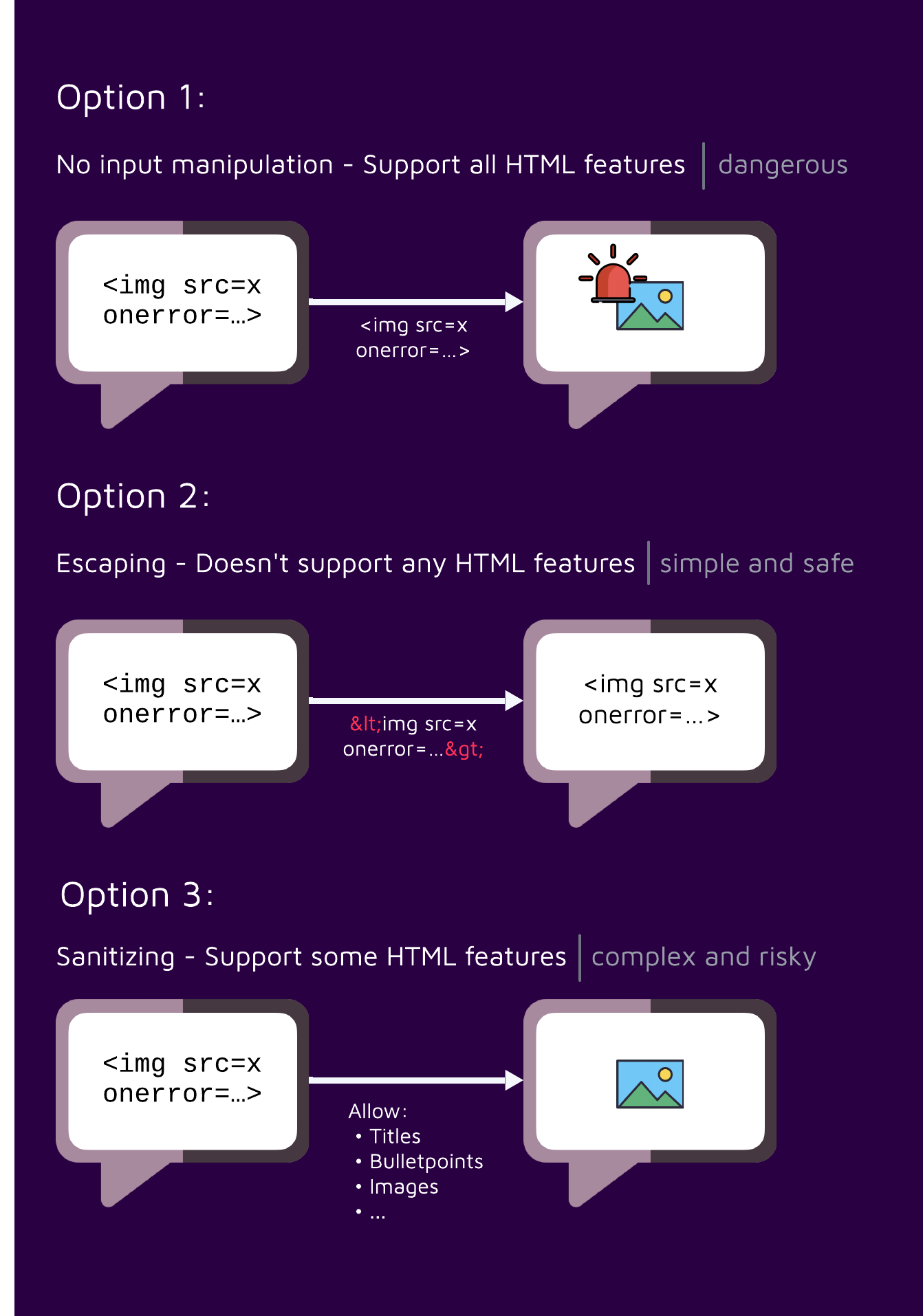

When a web application receives user-controlled input, such as comments or form submissions, it’s essential to ensure that this input is safe before displaying it to users. This prevents malicious code, like JavaScript, from being injected into the page and executed, leading to potential XSS vulnerabilities. One straightforward approach is to escape every character that has special meaning in HTML such as lower/greater than signs (<, >), but more often than not web applications would actually like to support HTML input from the user to a certain extent, such as allowing titles, images, and bullet points.

To strike a balance between security and functionality, web applications often need to implement techniques that allow for certain HTML elements and attributes while still protecting against harmful content.

HTML Sanitizers as a solution

A sanitizer is meant to clean HTML input by removing or modifying potentially harmful elements and attributes. It helps prevent cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks by ensuring that only safe, trusted content is rendered on a web page. Sanitizers are often configurable, allowing developers to specify which elements and attributes are allowed. However, the more elements and attributes that are permitted, the larger the attack surface becomes, increasing the risk of XSS vulnerabilities.

How do HTML Sanitizers work?

At first, the user’s input is just a string with no extensive meaning. So, how do the sanitizers know what to do with the data?

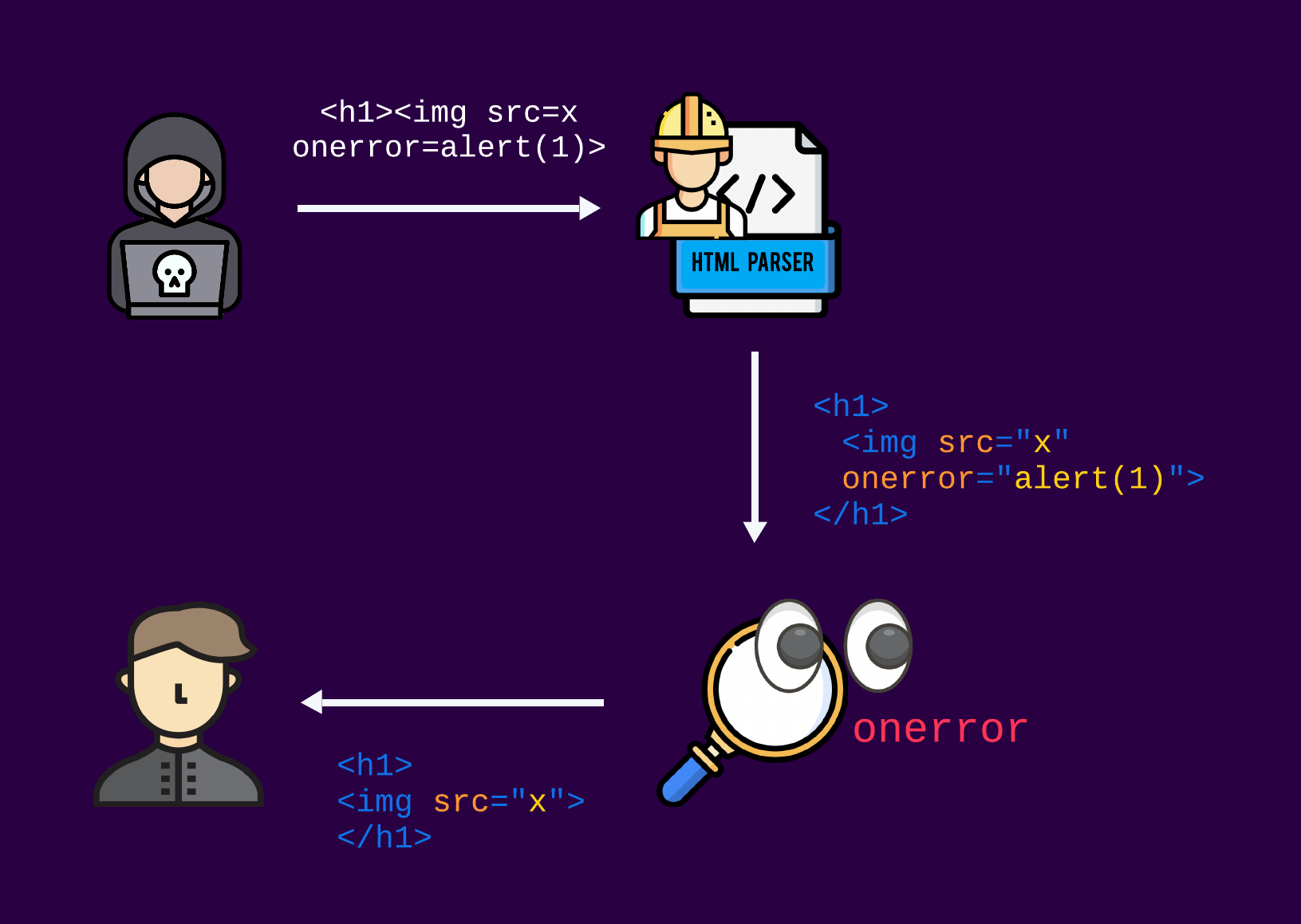

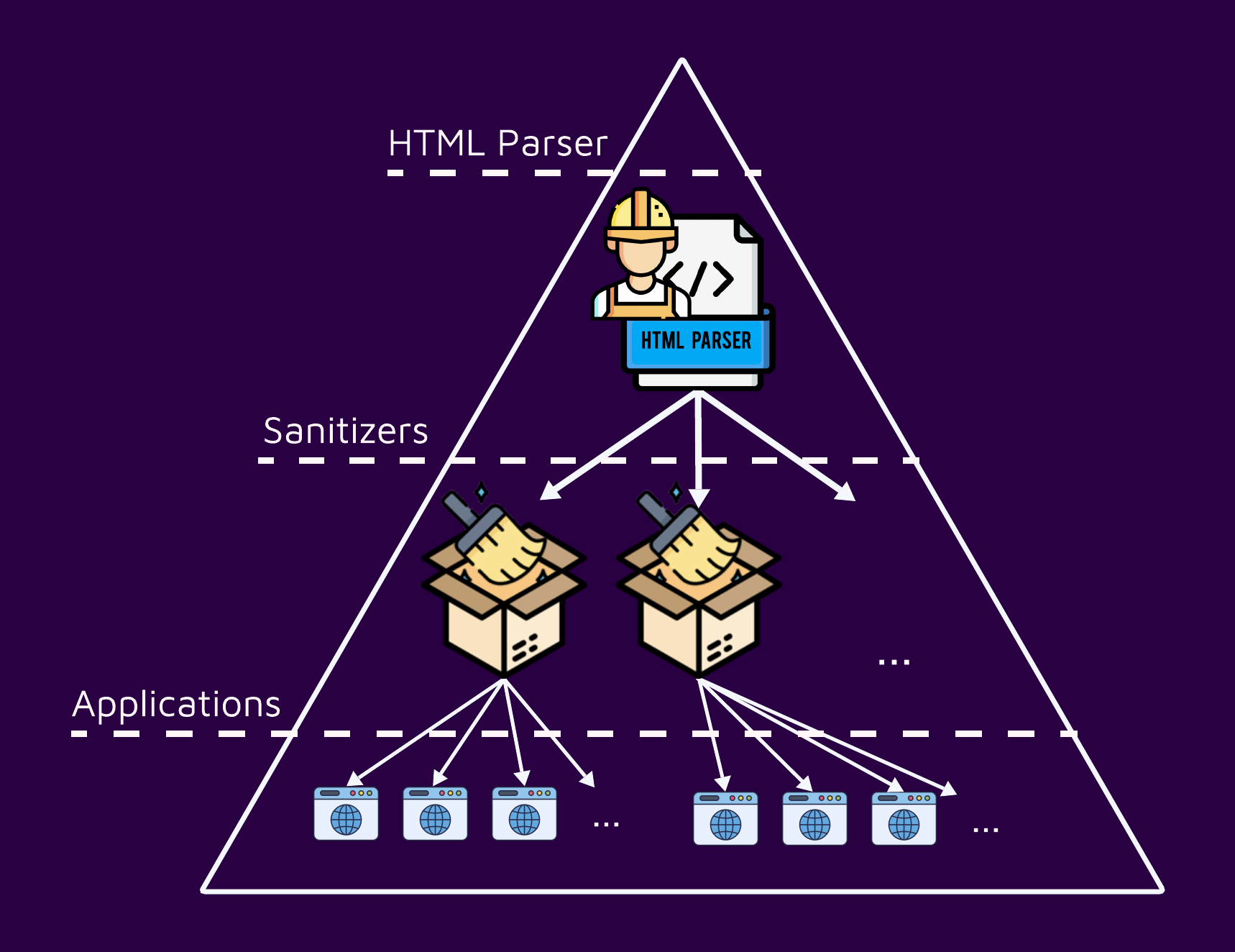

To simplify matters, the “magic” behind the scenes that enables sanitizers to manipulate the data in a smart way works usually by first parsing the untrusted HTML input to create a structured DOM tree object. This tree represents the hierarchical structure of the HTML elements and their attributes. Once the DOM tree is built, the sanitizer can iterate over it, examining each element and attribute. Based on its configuration, the sanitizer can then remove or modify elements and attributes that are considered unsafe or potentially harmful. This process helps ensure that only trusted content is rendered on the web page, preventing malicious code from being executed.

Which client side?

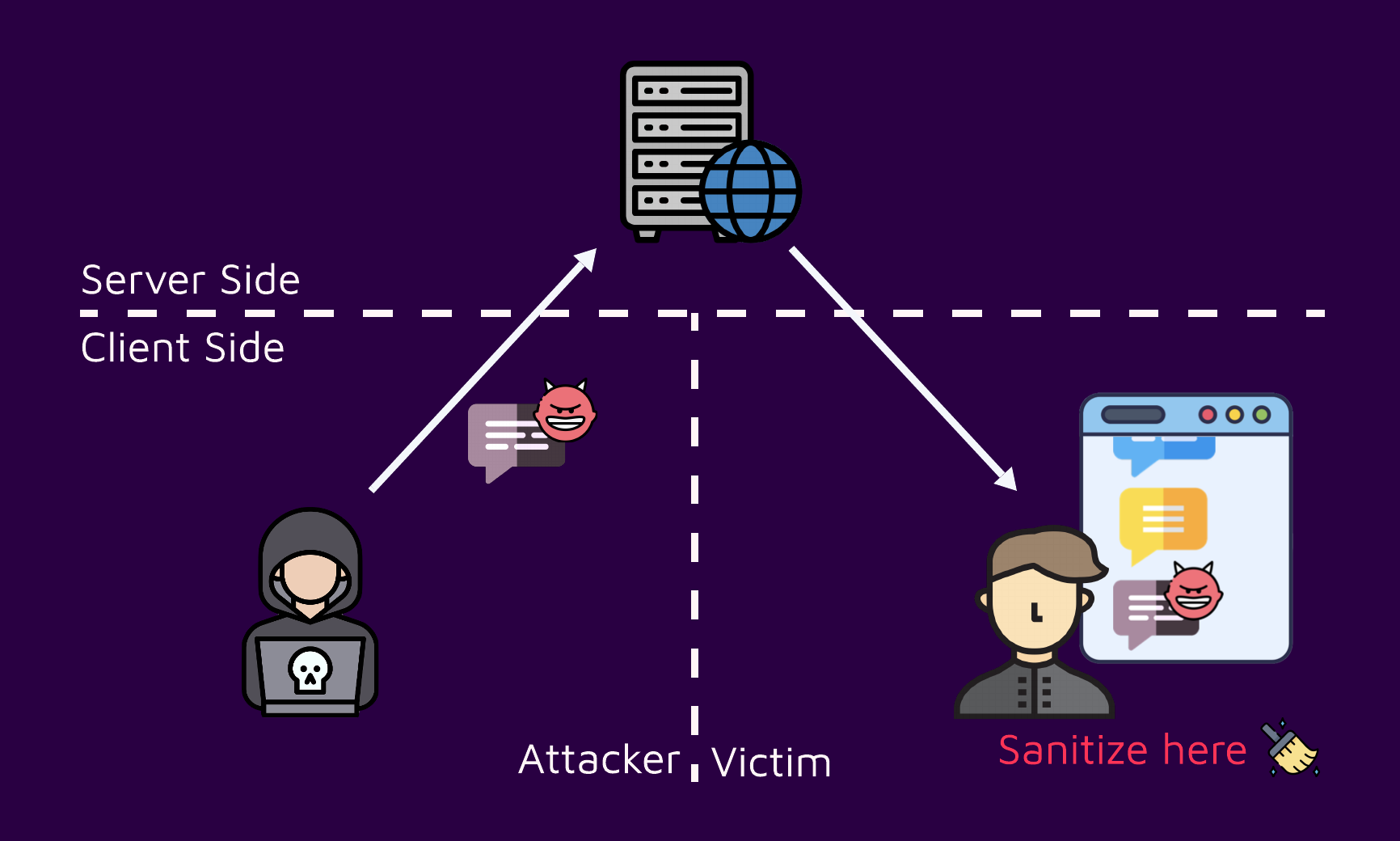

Let’s clarify a bit about the sentence “sanitize client side.” Considering a simplified XSS attack flow graph, there are generally three parties involved.

Attacker: The one that generates the malicious input, whether it’s creating a link or posting a comment on a forum

Server: The node that serves the vulnerable page containing the malicious payload in it

Victim: The end user who views the page, and triggers the execution of the vulnerability

On the client side, there are two parties: an attacker and a victim. Of course, sanitizing on the attacker’s client side doesn’t make sense because any code running on their machine can easily be bypassed, meaning they don’t have to obey any local rules.

Other traditional vulnerabilities, such as SQL injection and Server Side Request Forgey (SSRF) are usually triggered on the server side, so it makes sense to sanitize the untrusted input where the vulnerability might take place. But XSS is triggered on the Victim’s machine (client-side), so as a best practice it should be sanitized there. We will provide a detailed explanation in the following section on the “why”.

Research Story

Throughout our exploration of sanitizer bypasses, we consistently observed parsing issues on the server side. Yet, it wasn’t until we discovered a more widespread problem that we recognized the necessity of communicating the importance of client-side sanitization to developers.

It all began when one sanitizer bypass pattern caught our eyes:

<!--><img src=x onerror=alert(1)>--><textarea><!--</textarea><img src=x onerror=alert(1)>--></textarea><math><style><img src=x onerror=alert(1)></style></math>And more…

At first glance, the amount of payloads bypassing the sanitizer might seem like a generally poor logic implementation. However, a deeper analysis revealed one fundamental flaw.

Can you spot the core issue? If you do, you are probably an HTML expert at this point.

Despite the variety of bypasses, they all share a common root cause. Let’s try another guess, but this time with a hint: These bypasses affected not one sanitizer but most ones written in PHP.

Can you guess the root cause now?

Taking a step back and considering the common steps of how sanitizers work, we noticed that the common denominator for vulnerable sanitizers is the parsing algorithm. In our case, most sanitizers we looked at written in PHP were using the built-in HTML parser. Given PHP’s primary use in web development, it offers an out-of-the-box HTML parser. Due to its convenience, it’s understandable why sanitizer developers opt-out to use it. However, if this parser’s behavior differs from the victim’s browser, it creates a discrepancy that attackers can exploit

So in what way was the PHP parser different from the browser that caused these bypasses? If we split the payloads by HTML features:

<!--: Comment<textarea>: RCDATA<style>: RAWDATA<math>: Foreign content…

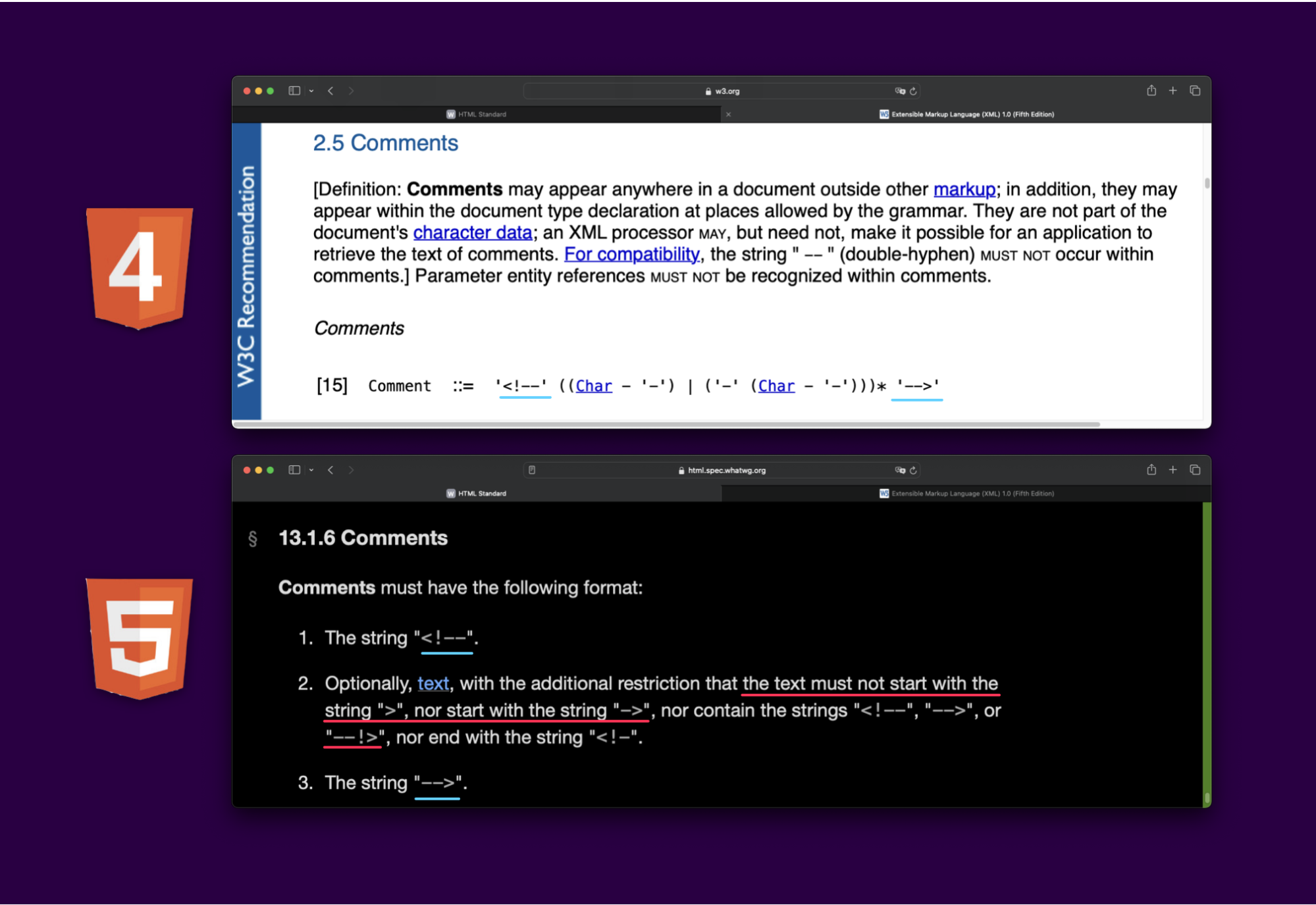

We notice that they are all either new or updated features in HTML version 5.

HTML5 represents the most recent major revision of the HTML standard. Introduced in 2014 and used commonly by today’s standards, it hosted new features and capabilities, including multimedia support, new elements, different namespaces, web workers, and many more.

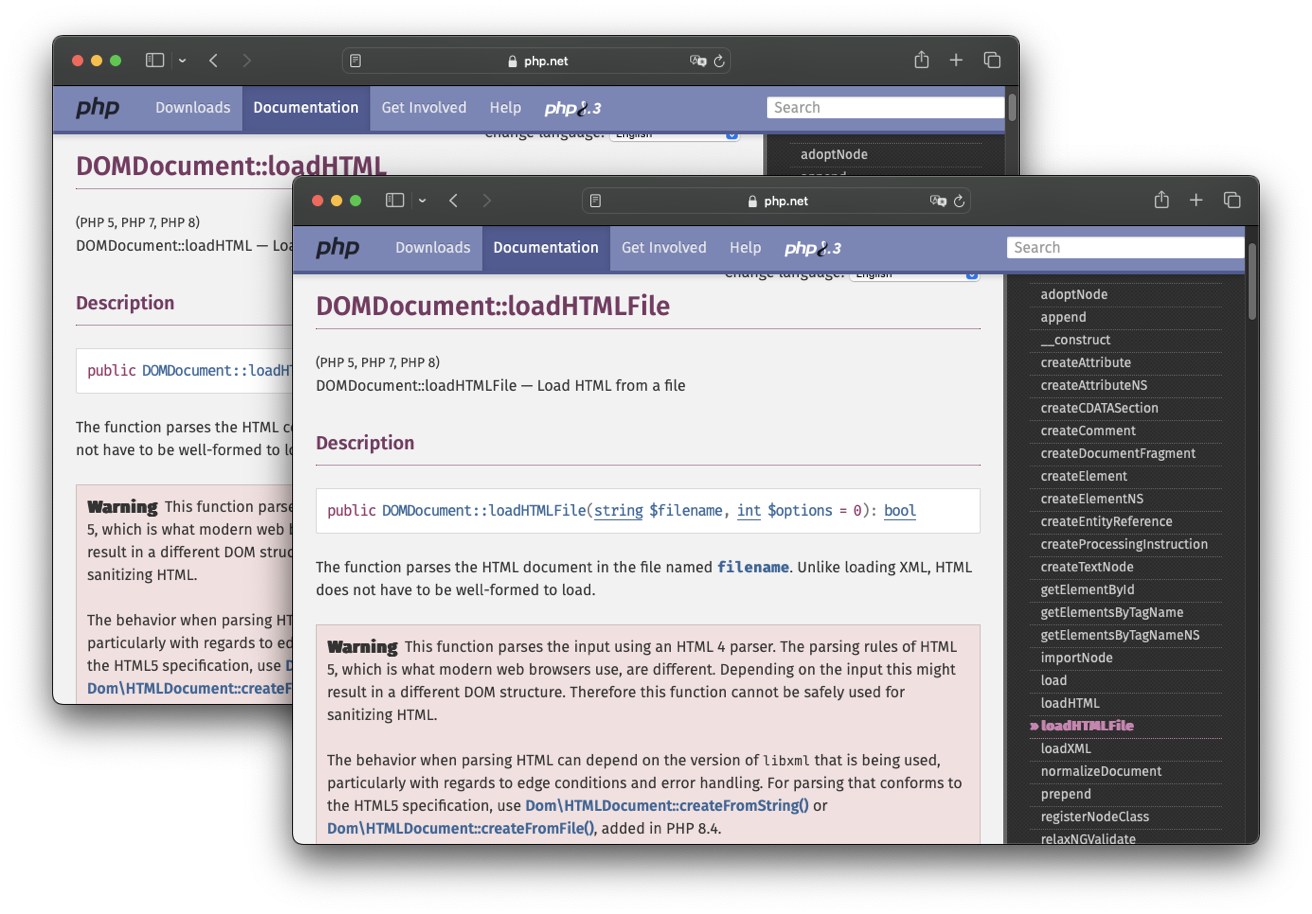

The built-in PHP HTML parser was using the underlying package libxml2, which only claims to support HTML4. So, subsequently, PHP was parsing HTML with the outdated HTML 4 standard from before 2014.

Differential Example: Comments

Let’s take a look at one example of a difference, comments. Pulling up HTML4 documentation, comments are simply starting with <!-- and ending with -->. But in HTML5 it states that “the text must not start with the string > nor ->“ and can be ended with --!> as well.

That means, most PHP sanitizers that allow comments (or any other specific HTML5 combination of tags) are vulnerable to bypasses.

On one hand, it is convenient and most of the time best practice to delegate tasks using prewritten code. On the other hand, this also means that one bug might affect many applications:

Sanitizers’ Achilles’ heel: HTML Parsing

It might seem like a big deal, potentially impacting many applications considering the wide spread of PHP. Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the iceberg. In fact, we encountered a third-party HTML5 parser written in PHP that included some differentials which resulted in bypasses of sanitizer that used the library.

The Challenges of HTML Parsing

With the evolution of the language and the introduction of features, the complication of HTML grew accordingly. Despite its widespread use, HTML is not always straightforward to parse. From backward compatibility to tolerance for errors, its flexibility can be a double-edged sword, leading to inconsistencies and unexpected behavior. The root cause of many sanitizer bypass vulnerabilities lies in a fundamental misunderstanding of HTML’s complexities and the various ways in which malicious code can be injected. Let’s try to emphasize this by giving a couple of examples:

General differentials: HTML is not straightforward to parse, to the point that even major browsers like Chrome and Firefox can have subtle differences in how they parse and render HTML. A server can have clients using various browsers, hence different parsing.

HTML is a constantly evolving language. New elements, attributes, and features are introduced regularly, making new differentials between up-to-date parsers and older versions. For example, one user might use an older version of Chrome that follows older specification standards.

Parser Configuration: The configuration of the sanitizer’s parser can significantly impact its behavior. For example, whether scripting is enabled or disabled can determine how certain elements are parsed.

Parsing Context: The context in which the sanitized data is used is crucial. A piece of HTML that is safe in one context might be harmful in another. For example, a

styleelement’s content behaves differently in different namespaces.Parsing Roundtrip: Even when using the same parser, there can be issues with parsing roundtrips. This occurs when HTML is parsed, modified, and then reparsed. The process of parsing and reparsing can introduce unintended changes to the markup.

MXSS Techniques: Attackers can take advantage of Mutation XSS techniques to bypass sanitization, taking advantage of the complexity of the HTML language (read more about it here).

All in all, a server can never be sure that the way it parses the HTML will be the same when it is viewed on a different machine. This is why it’s important to parse and sanitize the data on the same endpoint where the XSS might take place.

What Should Developers Do?

Unfortunately, at the time of writing, there is no standardized, browser-native solution for securely handling untrusted HTML input. Currently, developers must rely on third-party libraries or build custom sanitization mechanisms.

While there’s an ongoing effort to develop an official client-side sanitizer (as we discussed in the Future section of our mXSS blog post), it is still in progress. In the meantime, the best approach is to carefully consider the specific HTML features required by your application. A more restrictive HTML policy can significantly reduce the attack surface, but it may not always align with product needs. For scenarios where some HTML input is necessary, DOMPurify is currently considered the most robust (When used on the client side) sanitization library. You can configure DOMPurify to only allow the HTML elements you need to further harden your application and prevent CSS injections as well.

Disclosure

Following our report PHP updated its documentation to contain a big red warning box on the HTML4 parsing API to raise awareness that it shouldn’t be used for sanitizing:

Additionally, in November 2023, PHP 8.4 was released with HTML5 support using the underlying Lexbor library. However, this still doesn’t solve the problem of not sanitizing the client side, as we’ve seen in the examples above.

Lastly, we reported our findings to various affected sanitizers. Some fixed our findings, and despite others not addressing our findings, we released this blog under the 90-day responsible disclosure policy.

Timeline

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 2023-09-19 | We report all issues to PHP maintainers. |

| 2023-09-19 | The vendor acknowledged receiving the report. |

| 2023-10-03 | The maintainers updated the official documentation to include a warning for developers. |

Summary

In this blog, we explored the importance of client-side sanitization for untrusted HTML input. We highlighted the inherent limitations of server-side sanitization, demonstrating how the complexity of HTML parsing can lead to vulnerabilities. Due to variations in parsing algorithms across different environments, server-side sanitization cannot guarantee consistent parsing amongst various endpoints. As a best practice, developers should implement client-side sanitization to ensure that untrusted input is processed in a controlled and secure manner, reducing substantially the risk of a sanitizer bypass.